Asian artists are hardly new to the global stage—but something feels different in Paris. Over the past week, as Art Basel returned for its fourth edition in the City of Light, there was a palpable energy in the air. From major prizes to quiet moments in galleries, signs of a more visible and confident Asian presence were everywhere.

Among them (but not limited to): Cai Guo-Qiang marked the Centre Pompidou’s closure for a five-year renovation with a monumental fireworks painting on its facade and China-born artist Xie Lei, who pursued his practice-based PhD in Visual arts at École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris from 2012 to 2016, was announced as the winner of the Marcel Duchamp Prize. I also saw “Stillalive,” a group show of Asian artists at Galerie Marguo. Amid a compelling presentation of emerging contemporary voices, the gallery borrowed a painting by Zao Wou-Ki, one of the pioneering figures who shaped art history in both China and France. The work served as a bridge between generations and a quiet nod to the past.

Installation view of the group show “Stillalive” at Galerie Marguo in Paris. Courtesy of Galerie Marguo.

Zao was far from alone. For more than a century, Paris has drawn artists from across Asia who helped reshape modern and contemporary art. Sanyu, Lê Phổ, Pan Yuliang, Tsuguharu Foujita, Whanki Kim, and later Yan Pei-Ming, Ma Desheng, and many more, each wove their cultural hybridity into the fabric of the city’s art history.

As I write this, I’m en route to Dijon and later to southern France, where Beijing-based artist Chen Fei is opening a solo exhibition, “Grand Lobby,” at the Consortium Museum, and artist Wang Ziping will be opening a solo show at Château La Coste in Provance.

Chen Fei.

Naturally, Asia Now, the Paris-based fair launched over a decade ago, remains a central pillar of this ecosystem. Among its many satellite events this year, one caught my eye—and appetite: a collaboration between Art Drunk Kitchen and artist Liang Fu, who brought Sichuan street food to l’Appartement Piaget, a speakeasy at the luxury house’s Place Vendôme apartment.

During my brief stay, many Asian professionals shared reflections on Paris as historically receptive, and how a more vibrant and connected community has emerged in recent years. Compared to cities like New York or London, Paris is often seen as offering a more livable pace and a lower cost of living. With that in mind, I spoke to several curators, artists, and dealers to better understand the shifts underway.

Liyu Yeo (right) with Kate van Houten (left), Takesada Matsutani (co-founders of Shoen foundation)

A Deference to the Past

Liyu Yeo, a Singapore-born independent curator who has lived in Paris for 15 years, is also the Ambassador of Asia Now. This year, he nominated four finalists for the Matsutani Prize and also helped the fair to curate l’Appartement Piaget.

Yeo first arrived in the city in what he described as his own Emily in Paris moment—to study French. Over time, he has witnessed a gradual shift in the city’s mindset. For him, two moments marked real change: the attacks of 2015, which fostered a sense of solidarity among Parisians; and Brexit, which catalyzed a wave of international galleries opening in Paris.

For Vanessa Guo, the founder of Galerie Marguo, another turning point was the Covid-19 pandemic. It was also a personal inflection point: she arrived in Paris just before the first lockdown, got stranded, and ultimately decided to stay. Leaving her position as senior director at Hauser and Wirth in charge of Asia, she opened her own gallery in October 2020. “Since then, Paris has changed dramatically,” she recalled. The pandemic, she believes, exposed both the vulnerabilities and the resilience of Asian communities globally. “It became a moment to reclaim presence and agency, to be seen and heard differently.”

Asia Now’s collaboration with Art Drunk Kitchen and artist Liang Fu, who brought Sichuan street food to l’Appartement Piaget

Since then, Guo has observed a clear shift in the city, including institutions and audiences beginning to understand that inclusion is not just about representation. “It brings new ideas, new energy,” she said. The momentum surrounding the upcoming Olympics, which took place last summer, only added to that energy. “Now, with Art Basel Paris in its fourth year, the city feels more porous, more curious, and more open to different cultural voices.”

Both Guo and Yeo have noticed a growing Asian presence in the city—not just demographically, but professionally across the art world. From students to curators to exhibiting artists, visibility is increasing. “The conversation is evolving—the structures are just beginning to catch up,” Guo observed. “The infrastructure around them is still developing, but it’s growing.”

Yeo believes that the Parisian art world has long been receptive to narratives shaped by Asian and diasporic voices, dating back to the early 20th century. He pointed to several projects on view during this year’s Art Week as proof of this ongoing legacy. Guo agrees. “Paris has long drawn artists from Asia here to redefine modern art,” she said, “and each of them brings their own form of cultural hybridity into the city’s story.”

Having spent time in other major global cities, Yeo reflected on what makes Paris distinct. “There is a marked difference between Paris and New York because of the social structure and history,” he said. “In Paris, one’s roots are an integral part of one’s identity. French family trees can be traced uninterrupted for hundreds or even over a thousand years. For that matter, when people in Paris talk about Asia, it will inadvertently contain a certain deference to the past.”

However, that does not mean that it must be a cultural cliché. Yeo sees young Asian artists working in Paris today whose practices are devoid of obvious cultural references: “They contain elements of personal history which sometimes evoke their cultural heritage.”

“I think this aspect of weaving one’s past into the present as one projects into the future is important in the way Asia is framed in Paris,” Yeo concluded.

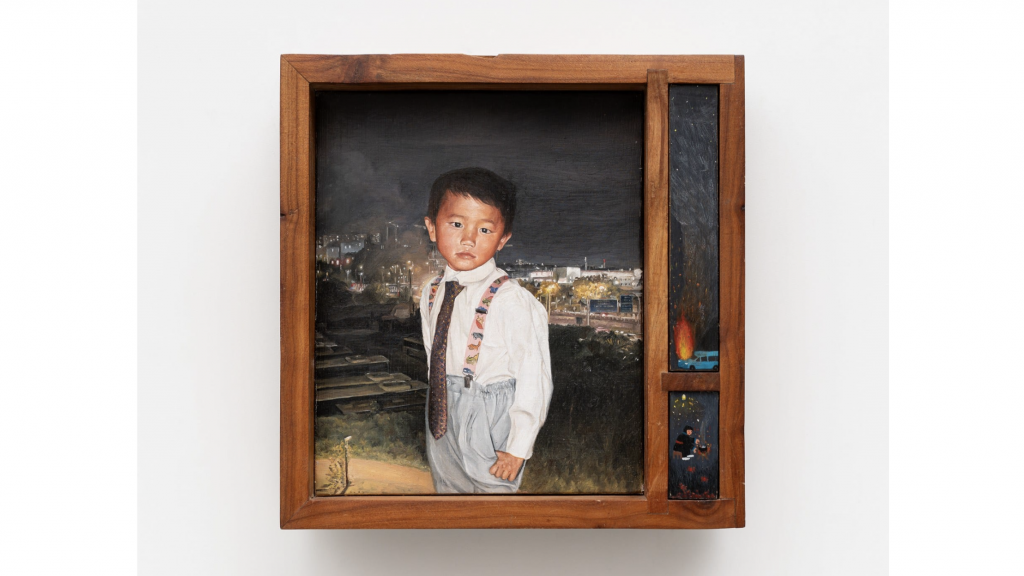

Alexandre Yang, Le Petit Prince (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Marguo Gallery.

An Absence Lingers

By contrast, Alexandre Yang, one of the artists featured in Marguo’s current group exhibition, offers a different perspective on what it means to grow up Asian in France. His story adds another layer to the broader picture. Born and raised in the rural north, Yang was encouraged by his parents to pursue a career in medicine. But in 2017, he quietly applied to an art school in Paris and moved to the capital, “after secretly passing the entrance exam,” he recalled.

Life in the French countryside came with its own isolation. “Unlike in Paris, we are very, very few, which does not make it easy for people to be open to us, even more so with Covid,” Yang said. Though his time in Paris has been intermittent, he has noticed a growing number of Asian artists in the city. Still, he pointed out a major gap: “There were very few French Asians in the country’s contemporary art (world).” This absence is especially glaring, he noted, in light of France’s colonial history.

Yang also highlighted the economic and cultural barriers: “Traditional contemporary art schools in France are difficult to access for people from low-income backgrounds. Money is also a barrier to cultural exposure.”

Alexandre Yang. Courtesy of the artist.

As one of the few French artists representing the Hmong community from Laos, Yang feels both a responsibility and a burden. “I want people to see my work holistically, not just as something ‘exotic,’” he said. While his self-portraits explore universal emotions like grief and family, they’re sometimes dismissed as inaccessible. He’s also encountered micro-aggressions, including having a red mark in his work mistaken for a political symbol.

“Some people in France aren’t used to seeing these subjects in painting,” Yang reflected. “Racism and micro-aggressions still creep in.”

Despite this, he remains hopeful. “I am very happy and excited to see more art from Asian people in Paris—French or not—as I think we need it to make the scene more diverse.”

Credit: Source link