It’s time U.S. arts leadership acknowledges that President Donald Trump and Russell Vought, his director of the Office of Management and Budget, have initiated a national arts strategy of seismic consequence, and to decide: will it answer with a strategy of its own? If so, authored by whom? Implemented how, and when?

The Administration’s arts strategy parrots tactics deployed in other arenas: a cascade of executive orders (EOs), grant rescissions, terminations, and threats designed to “flood the zone,” disorient leadership, sow division, compel self-censorship, and halt effective response.

This salvo has been largely successful. In fact, merely nine months in, the Trump administration is poised to become the most consequential, effective arts presidency in American history—peerless in impact since at least Johnson, whose pillars this administration has toppled with surgical efficiency.

Brett Egan. Courtesy DeVos Institute of Arts and Nonprofit Management.

It’s tempting to view the administration’s approach as haphazard. But careful analysis reveals a coherent, if unspoken, national arts policy—one defined by values, mechanized through institutions, backed by capital, and enforced by savvy loyalists.

A Multifaceted and Aggressive Policy Agenda

The Vought/Trump policy is discernible in three sleeves:

Aesthetic. The administration has quickly sought to exert clear aesthetic preferences throughout the public realm. In August, Executive Order 14344 directed the General Services Administration (GSA) to not only favor “traditional and classical” styles in federal building architecture, but to actively shun modernist, “contemporary,” and brutalist themes. As chair of the Kennedy Center, the president has argued, in some detail, the merits of specific Broadway productions; sought a curatorial role in the Center’s mainstage programming; and personally selected this year’s honorees, dismissing “plenty” of otherwise qualified candidates who were “too woke.”

The administration has initiated the largest federal art program in recent memory, the National Garden of American Heroes, commissioning 250 statues for $200,000 each, but not of any design: only those “life-sized” statues proposed in marble, granite, bronze, copper or brass were considered. The Oval Office has been embroidered in gold, and the incipient White House Ballroom promises an equally florid, “golden ballroom” vibe. These actions are but a few of numerous, forthright actions taken by the administration to advance an explicitly Eurocentric, classical, realist aesthetic.

President Donald Trump signs executive orders in the Oval Office on January 20, 2025 in Washington, D.C. Photo: Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images.

Ideological. The administration has swiftly realigned federal arts agency decision-making to its social ideology, with broad downstream impacts on the independent sector. EOs 14151, 14168, and 14173 were interpreted by Endowment leadership to justify elimination of federally funded speech on issues including diversity, equity, inclusion and gender. While the constitutionality of these actions is debated in court, grant-making priorities have been rewritten, and a virus of self-censorship has infiltrated America’s philanthropies and cultural institutions. Interim Kennedy Center management has moved to eliminate “woke” attractions and introduce religious (specifically, Christian) programming.

And, in August, the administration’s detailed critique of specific Smithsonian exhibits joined demands for their removal, and similar directions targeted national park signage addressing topics such as climate change and slavery, citing their “improper partisan ideology.” Broadly speaking, an ideology skeptical, or openly hostile, to the principles of equity, inclusion, diversity, and critical historiography has taken root throughout the federal arts infrastructure.

A sign marks the entrance to the Smithsonian Arts and Industries Building located along the National Mall on August 20, 2025, in Washington, D.C. Photo: J. David Ake/ Getty Images.

Economic. The administration has enforced its aesthetic and ideological preferences through correlating economic policy. It quickly rescinded billions from the arts, public media, libraries, and museums, and redoubled proposals to eliminate the NEA, NEH, and IMLS. It simultaneously redirected some funding to preferred projects, including the Garden of American Heroes, initiatives that celebrate military history, and projects “that explore the role of the United States as a leader in global affairs, emphasizing themes of American exceptionalism, moral leadership and America’s national interest.”

Through the One Big Beautiful Bill, the administration ushered the largest Kennedy Center appropriation in history—to refashion its grand halls in alignment with the administration’s preferences. Significant tax code changes have emboldened lower-dollar donors, while disincentivizing larger donors and corporations, with most estimates projecting a net negative impact on the nonprofit sector. Broadly speaking, the administration’s economic policy will weaken the nonprofit arts sector’s ability to function—including in its historical role as a potent critic of dominant official narratives regarding national identity.

The Arts Sector Lacks a Unified Response to an Aggressive Policy

The administration’s swift appointment of loyalists to key positions illustrates a level of priority on arts and culture unprecedented in the modern era. Just 23 days into his term, Trump and Richard Grennell replaced Chair David M. Rubenstein and President Deborah F. Rutter at the helm of the Kennedy Center. On day 51, Michael McDonald was named acting chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities. On day 59, Keith E. Sonderling was named Acting Director of IMLS. And, on day 106, Mary Ann Carter was nominated Chair of the National Endowment for the Arts, a move that took Biden 258 days; G.W. Bush, 719; Obama, 142; Clinton, 199; Reagan, 267; and Mr. Trump, in his first administration, 726 days.

Keith Sonderling was sworn in as acting head of the Institute of Museum and Library Services. Photo: Rita Franca/Nur via Getty Images.

Under these appointees, Trump’s priorities have been executed at a swift pace, while the professional staffs of all three agencies and the Kennedy Center have been hollowed. It is an open Beltway secret that final consolidation of the agencies is imminent likely via merger—assuming they survive the budget season intact.

These actions have stunned our diverse sector, whose diffuse leadership remains undecided on how to respond.

The inertia is understandable: our sector—historically circumspect of consolidated leadership—remains all spoke and no hub, with little precedent need to organize policy and action. However, we must now acknowledge that its noble commitments to grassroots inclusion, diversity of thought, and representation have limited its ability to quickly mobilize with coequal force to the administration’s agenda. While our sector debates organizing methodology, leadership structure and a shared platform, the administration implements a uniform vision with searing force.

Green Shoots of Resistance, But a Focus on Yesterday’s Challenges

To be sure, flashes of courageous resistance and important, if nascent, efforts at collective response are afoot. In September, Smithsonian secretary Lonnie G. Bunch III sidestepped White House demands for curatorial changes by launching an autonomous internal review. In October, 100-plus philanthropies locked arms to rebut the administration’s claim that they support domestic terrorism. Rhode Island Latino Arts v. NEA persuaded senior U.S. district judge William E. Smith that the NEA’s move to penalize projects for “promoting gender ideology” constitutes illegal viewpoint discrimination.

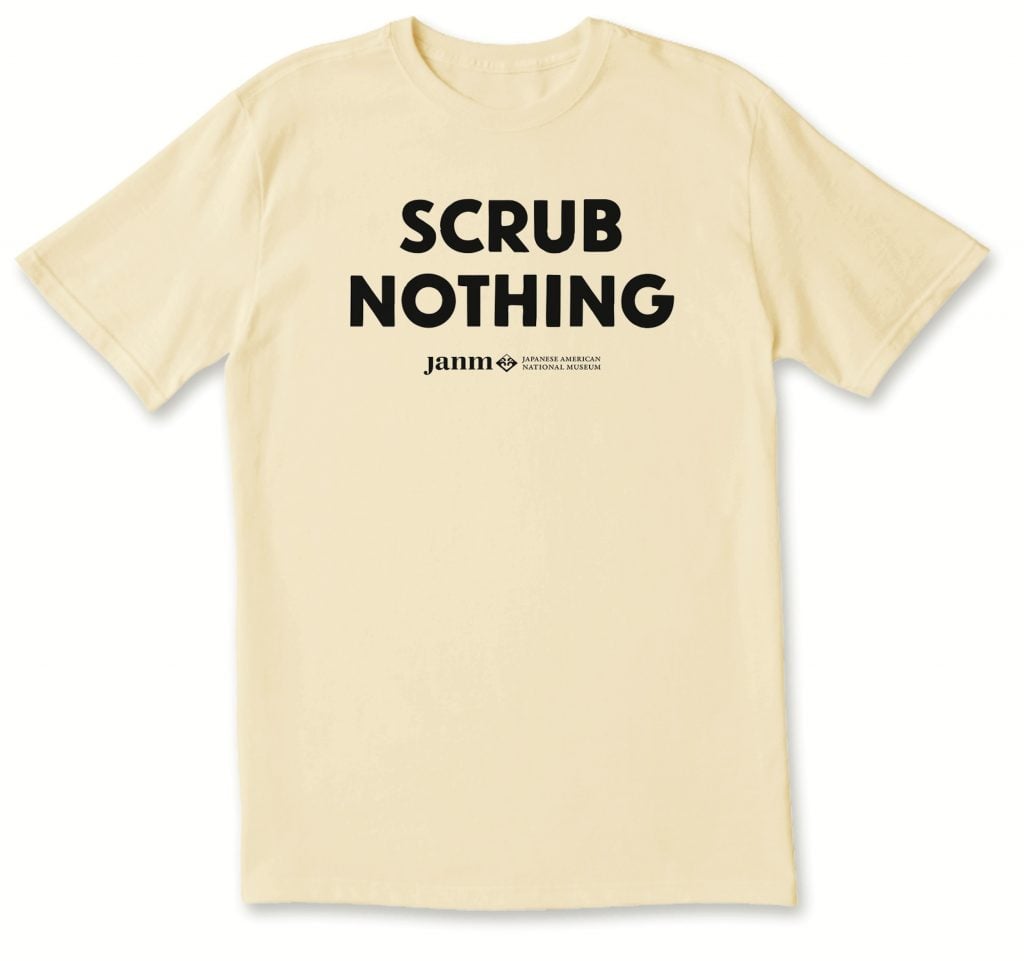

The Future Film Coalition is organizing filmmakers, exhibitors, and distributors to defend independent cinema; Jane Fonda has revived the Committee for the First Amendment; organizations such as the Japanese American National Museum have taken a bold stance against self-censorship; national advocates have issued principled statements; and following Elizabeth Larison’s clarion call, the National Coalition Against Censorship’s Arts and Culture Advocacy Program issued “Cultural Freedom Demands Collective Courage,” which has gained some traction.

A t-shirt created by the Japanese American National Museum in response to the Trump administration’s orders to “scrub” language relating to efforts at diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) at all federally funded organizations’ websites. Courtesy the museum.

In truth, however, the lion’s share of sector advocacy has focused less on today’s frontline crises than on yesteryear’s Maginot Line: federal funding for the national endowments and IMLS. Preserving the agencies and their appropriation matters, and the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies, Americans for the Arts, and the American Alliance of Museums have each organized maximum effort to secure their survival. But as I argued in July, even if the agencies are preserved, they are no longer the noble investments envisioned by the Great Society but, rather, diminished, increasingly partisan instruments.

Future-year funding is likely to remain meagre (this year marks the NEA’s lowest allocation vs. GDP since its inception) and, at least for the next several years, advance Trump’s priorities. At the very least, I suggest we must develop means aside from the tax return to engage Americans in a discussion about nonpartisan, national support for the arts (and libraries and public media). And ultimately, arts funding, while crucial, is just one front in this contest; while the administration plays the board, we’re focused on a single square.

What Could a Nonpartisan National Arts Policy Look Like?

The National Endowment for the Arts headquarters in Washington, D.C. Photo: Graeme Sloan / Sipa USA / Alamy Live News.

What’s needed now is an independent, nonpartisan, national arts policy of a sweep and potency on par with Trump’s. In this effort, four difficult but attainable tasks are urgent:

1. Author an independent sector national arts policy, by and for the American people

A plain-language platform is needed to articulate the importance of arts, culture, and creativity to democracy, economy, and healthy society; commitments to free expression, universal access and equal representation; future roles for the arts in education, health, and urban renewal; pathways for artificial intelligence to become an ally, not adversary, to the arts and artists; and optimal roles for government, the private sector, and the people in the advancement of these goals.

2. Form an effective leadership entity

Representatives from the aforementioned institutions can form a hub entity, or “congress,” with a mandate from their memberships to operationalize this policy through collective action. This congress would encourage—but not compel—its memberships to support national policy objectives. Semi-annual meetings would function as a platform to organize, initiate new campaigns, promote new voices, and debate policy amendments.

3. Define messaging

Concise, comprehensive, compelling messaging on the value of the arts in America—to a thriving democracy—should be defined and distributed through all willing vehicles aligned with this congress.

4. Stand up an independent, nonpartisan national arts fund

The congress can appeal to national foundations, corporations, and individuals to develop a nonpartisan nonprofit to supplement (not replace) public funding, perhaps as defined by my July proposal, through a vehicle such as that proposed by Alan Brown, a combination of the two, or another, better model.

In such an effort, there would surely be vigorous contest over the nature of leadership, particulars of policy, and who speaks for whom. But we must be candid about the alternative: without a shared policy, backed by capital, and implemented at scale and en masse, Trump’s policy will deliver, effectively unchecked, the most consequential arts presidency in American history.

It is hard but now necessary to accept that Trump’s unprecedented focus on arts and culture presents sector leadership with a once-in-a-century opportunity to meet the moment with its own vision for the future of art in America.

Brett Egan is president of the DeVos Institute of Arts and Nonprofit Management in Washington, D.C.

Credit: Source link